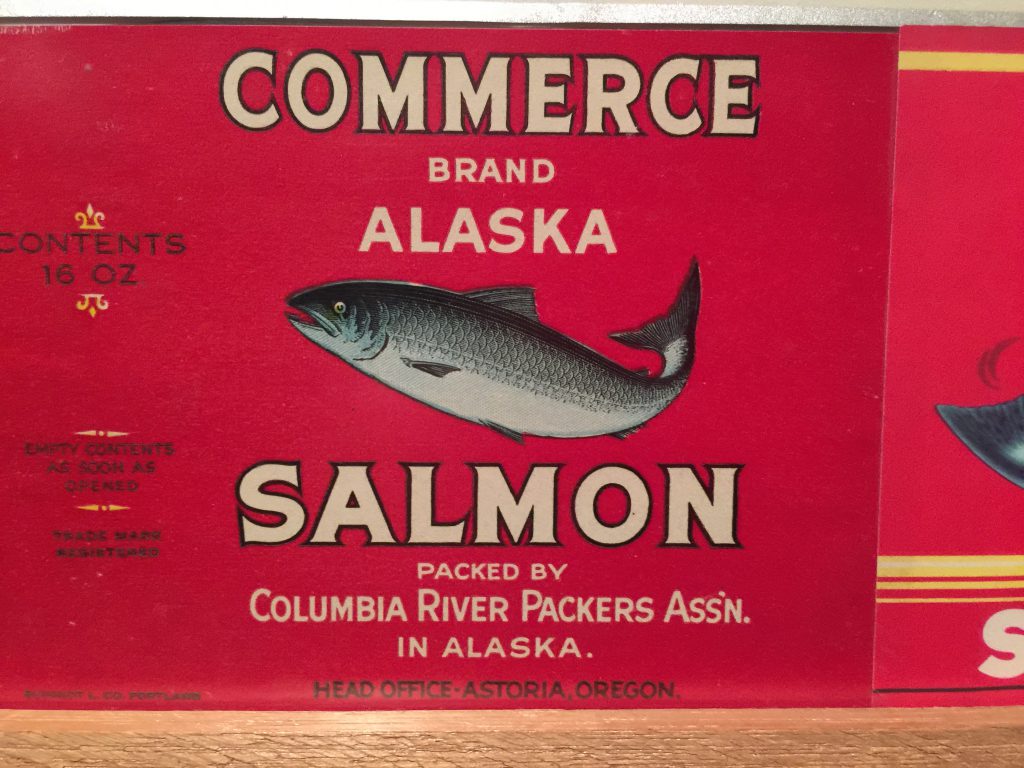

Fishermen utilized many methods to ensnare salmon, including fishwheels, horse seining, gillnets, and traps. In the early years, these practices were mostly unregulated and left to the determination of the fishermen themselves. Chinese laborers and foreign workers were largely excluded from salmon fishing. Some worked in canneries, but were generally viewed as greedy entrepreneurs and often blamed for the depletion of salmon runs.

One of the principal reasons for the decline in salmon was simply that the more the markets demanded, the more the fishermen provided. As competition among fishermen increased, battles erupted among salmon fisheries over equipment use and fishing rights. Fishermen petitioned government agencies to prohibit certain types of commercial fishing practices and to restrict fishing in certain areas. As fish runs declined, artificial propagation was considered as a viable alternative to save the salmon.

Cannery operators believed the salmon supply to be endless, and as a consequence, the salmon industry quickly grew wasteful. Not only were large portions of the fish discarded, but also many complete species of fish were discarded, as the fishermen caught more fish than the canneries could process.

During the spring and summer seasons, often the canneries processed only Chinook salmon. Canneries dumped other species back into the rivers. In 1895 it was estimated that 7 million pounds of fish were discarded. By the 1890s the fish population was declining.

By the turn of the 20th century, early conservationists began to sound the alarm that salmon runs were being depleted. In addition to the effect of natural environmental conditions and depletion of fish stock, the influence of logging, mining, irrigation, and commercial fishing were being felt. Rapid deterioration of fish habitat became evident in the early pollution of the rivers and spawning streams. By the 1930s, large-scale dam projects posed additional barriers for migrating fish.