The most hurtful circumstance about sorrow is the way it invites the crowding in of memories of happier times for poignant comparison with one’s present misery, and I was miserable.

I am standing, anxiously dancing really, on a clammy flak jacket in the bottom of a partially flooded fox hole in the north central jungles of Papua, New Guinea.

If you know New Guinea, I am south of Madang and northwest of Goroka. The jungles here are mainly estuaries of the mighty writhing Sepik River which empties down river near the village of Wewak. It took our squad two weeks to hike into this village, Kamindibit, on the banks of the muddy Sepik, from the north coast. Here we set up a radio outpost.

I am looking up at my master, Jinrin who sits opposite me in our tiny foxhole, with his head hanging down and his arms resting on his bony knees.

His looks at me are morose, dejected, and inquisitive, I am his eyes ears and nose. I am a war dog. My role is to protect my squad. I am very hungry and beyond thirsty, as our last morsel of food was yesterday of stale soy-soaked rice crackers. My last drink was gulping urine and blood laced water from the bottom of our shallow fox hole.

Desperation reigns.

There is no dry place to sleep, in fact there has not been a dry place to sleep in weeks. The oppressive jungle weeps, steams, flowing water everywhere, even, it seems, up from the ground. The ground is wet and muddy, and the sky is wet and muddy, they mirror each other, a dirty photograph.

Leeches, spiders, and immense rain-washed shiny black crabs are everywhere. Jinrin wrenches down his soaking flight pants and pulls off blood sucking leeches. He is petrified with fright; sometimes he just stares in fearful disbelief at Kenzo his cadet school buddy, now lying dead, his former ground navigator. “Time and events rob us of all”

It has turned pitchy bitter-black as I tell you this, jungle sounds are close and near while boiling jungle rain falls in sheets. The final sunset was out for a few moments ago, cracking the grey clouds like a golden samurai sword. The little bit of sky that I could see in that instant was tangerine and blue. Flocks of orange and indigo parrots, yellow and red parakeets all were flying over in neon tetra formations.

All has changed. Night, near the equator, has fallen like a Kabuki stage curtain. A scimitar of a moon shows, disappears, and shows again and again vanishes devolving to rainy impenetrable black.

Close and fetid, in the gathering and fearfully projecting darkness I hear the rasping sound of the great leather bill’s coarse wings rubbing against the leaves nearby in the very dangerous jungle, as it settles into roost for the night. All birdsong ceases with the darkness, except for two owls singing their same song over and over and over until I think I am going to go nuts. The owl or Fukuro brings our people luck against disaster, but I’m not feeling lucky at this moment, in fact, just the opposite.

Lying, thrashing, and squirming beside me is Big Hiro, the only other dog in our small squad of four. Hiro moans and cries, he has been shot by Jinrin Matabushido, my master.

Mr. Matabushido shot Hiro then he turned and leveled his Nambu 94 the so-called suicide, pistol on me. He was crying, and yelling, “Shizukani shiro little Hiro, shut up!” as he waved the Nambu in my face. I stood dead still, Jinrin’s eyes were crazed his hair was wet and plastered against his brow, he was raving.

As his eyes frantically roved the dark jungle around us, he occasionally shivered then murmured “Iyami!” That is his mother. I know her well. She is charming and very far away.

On many afternoons I sat on her lap in her exquisite bamboo garden as she absentmindedly pets my little white head. She stared off listening to the crickets in a small delicate bamboo cage hanging near-by from the Katsura tree. She told me stories of her husband who was an officer on the gigantic battleship “Yamato.” She told me about Jinrin when he was a little boy, he was always nervous she said.

At those long-ago times she fed me little dainty bits of sweet bean curd, a minute nothing of whipped cream from her exceedingly long painted fingernail, a small grouse leg with soy. Well, I don’t like to admit it, but I was spoiled in those days, but now? No, now that is all over.

Some nights, when I can sleep, I still bark and moan, my legs jump and run and then Jinrin wakes me up to keep me quiet. When he awakes me, I for just a moment, can still smell the sweet summer grass of our garden and the fresh salt air of Hiroshima.

This sweaty night, unlike many others, was quiet, though there was still the occasional burst of machine gun fire. Back in the inky dark someone screams in Japanese, “Kotchi!” (“Over here!”), and then a grenade.

Jinrin was babbling at me loudly again. He didn’t need to shout at me: humans forget that we of the dog family have very acute hearing, a whisper works as well or better than a shout.

Jinrin was frightened, I could hear it in his voice. He was afraid that Hiro and I would make a noise and the enemy would find him. The bursting grenade made Jinrin moan.

His ground navigator lies desperately slumped against the sandy grainy sides of the shallow foxhole, his eyes open staring, his fires out, what I mean is he is dead. His rigid hand is held high clenching a dagger, frozen in place by the breath of “Shinotenshi,” the angel of death.

When the navigator was first shot, I crept up to him and smelled the wounds then I licked them thinking I could make him better, it didn’t help. Earlier he had taken two sniper rounds, BANG BANG, in his neck. Quietly he pumped and pulsed jerked and jumped and bled in spurts out into the foxhole, my feet first were the bright red of fresh steaming blood, now my feet are black from the navigator’s stale coagulated blood. He died instantly, Jinrin screamed, and backed as far away from the navigator as he could get in that small sad foxhole.

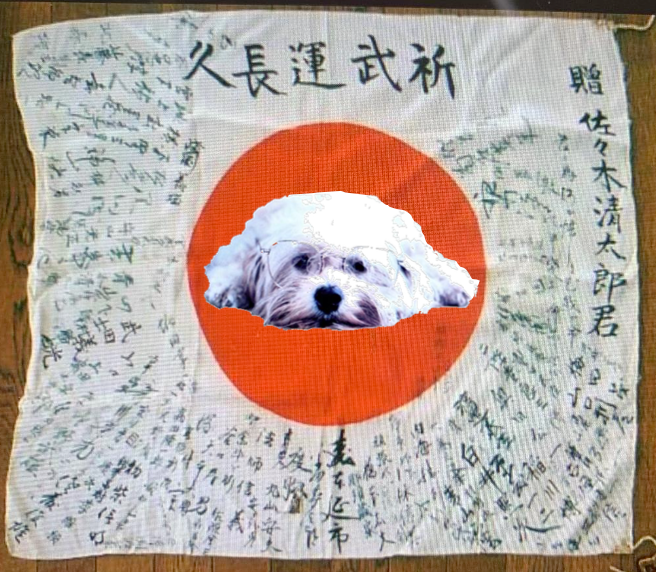

Normally back in Japan, on our estate near Hiroshima, Mr. Matabushido, as the servants called, Jinrin, was kind of a young emperor to all of us on the estate, he was gentle. Jinrin, which is what I called him, was a Seventh Generation Kenmasuta, a sword master. Everywhere he went I went with him, we were inseparable. I slept with him with my head on his pillow on his tatami mat. I rode behind him on the rump of his great white horse. So given this, it seemed natural that when he sailed for war in the south Pacific, that I, trained by Jinrin to be a warrior dog, that naturally I would sail with him.

His friends scoffed and derided the presence of a little dog, such as me, at war, “why that runty dog doesn’t weigh more than two pounds.” So, a comment here, I wasn’t runty: I was big for my breed, my hair was glossy and pure white. Jinrin used to laugh and say he could find me anywhere because of my whiteness.

My mistress, Jinrin’s mother, as I mentioned, fed me, and fed me well. I had tofu steamed, small roasted birds, cow’s milk, and apples. Don’t ask why but most dogs don’t like apples, but I did. I was small but strong and well fed.

“Look at how small his teeth are,” and with this, God damnit, some noble or other, would lean down and pick me up and then try, what the hell, to pull back my lips with his dirty fingers to look at my teeth? I’ve got my pride, I bit them until they bled. Small doesn’t mean helpless, it doesn’t mean that every schoolboy or stump dumb adult that comes along dragging a rock, can have their way with me.

Jinrin’s father, Shiki Kenju, use to tell Jinrin, remember my young son “Courage grows strong at a wound.” No one has heard from Admiral Shiki Kenju. Everyone is frightened to talk of him for fear of “Fuun” — bad luck!

Some civilian from time to time, asks Jinrin, why take that dog to war? Why? I can answer that, because of my senses, right now as I am telling you this, I can smell the enemy, they don’t smell like we Japanese, and they are infiltrating. The heated rain has stopped for the moment and the sopping jungle drips menacingly, so much so that I can’t tell if it is enemy infiltration or innocent water running off a gigantic jungle leaf.

The little sounds drive me to distraction, I am the guard dog and in the dripping jungle I can’t tell one subtle sound from another. The cloyingly sweet and putrid humid air shouts danger to me, I can smell the pungent sweat of the white creeping menacing enemy, too nearby.

Humans forget a lot about us dogs if they ever knew anything to start with. Fact is, most people know very little about how we think, how we hear, how we scent the world around us how we can love and how we can hate when mistreated. We are not little people rather we come from a long and equally distinguished family as humans. It is not an exaggeration to say that without us dogs you humans would never have gotten so far so fast in this world.

I just heard a branch snap in the gloom.

Where was I oh yes, we terriers love people however we are not people. The relationship between us dogs and humans is a bond going back to the beginning of time. If you wish to understand the story of our beginning, step out into a wilderness some night, and listen to the sobbing of a wolf. Now that is a story told.

Love. There is a type of love that gives everything and asks nothing. My great, great, great, great, grandfather Buto was of this type.

When Buto’s old master Tomio-O died, Tomio-O was the benefactor of the famous Golden Tsutakawa Temple. This temple was on the straits of Itsukushima, Tomio-O was very wealthy and an icon, in Japan.

On the day after his death, Buto followed the funeral procession to the temple where his old Master Tomio-O was to be placed in a carved and sculptured niche with stone Palace Dogs on each side. The funeral procession was long and winding with wafting incense, flutes, gongs, holy words, colorful flags and streaming banners, the family following loudly wailing, handing out koden– condolence money.

With incense still smoldering and the elaborate ceremony finally over, the formal and somber crowd left in tears and resignation, Buto stayed.

He was finally scooped up by a family member and taken back to the castle where later that night he crept out setting off along the seafront lanes for the Temple again and there lifting his small white muzzle to the sky, he stayed howling and moaning, beside his master’s grave, until he died five days later of starvation, he refused to eat. Some say he died of a broken heart. We highland terriers are known for our strength but then no one can live forever with a broken heart, not even a powerful little terrier like Buto, my great, great, great, great, grandfather.

“Midnight shakes the memory,” darkness was now everywhere, sadness was slashing and pointed.

Sitting, uncontrollably shaking, and shivering in the fetid water I raised my nose and smelled once more the sickening sweet stink of the enemy, it was getting stronger. His ghastly stench swirled everywhere in the damp decaying jungle. Just the other side of the ragged torn lip of our fox hole was death, I could feel it.

I could also hear the enemy moving in the darkness of the jungle nearby. The rain started again drumming the tops of the gigantic dark green leaves. Something else, I could smell another dog, not Big Hiro, who now had died. I will miss him! He was loyal.

I looked up at Jinrin, softly whining, and as I had been trained to do by him, quietly pointed my nose in the direction of the approaching enemy, and then looked back at Jinrin. I did this several times, the water from his helmet dripping on my face.

Noticing my warning, he quietly and slowly took off his helmet and reaching down inside his quilted jacket, he pulled out his glasses and put them on. Even when he was a little boy, he had poor vision. He always wore thick silver rimmed glasses. I was his vision, day, and night, without his glasses he was near blind. When we were in Japan on our estate, he sometimes would hold me up in the air above his head so I could locate our cattle for him.

He reached down and picked up his Nambu-94 and cocked it.

At that exact moment when he put on his glasses the low dirty clouds parted just for that instant and the full moon shone clear. Crouching lowly, Jinrin seized this moment of moon light, to peer over the edge of the shallow foxhole into the dimly lit jungle. The world outside of our foxhole, was wet and filled with disturbing pockets of blackness and the end of time on earth. How can one tell our time that’s left?

Jinrin gasped like he was going to say something to me, then he suddenly collapsed backward into the flooded foxhole, his head only a foot or so away from where I crouched. He opened his eyes, looked at me warmly and said, “Oh Little Hiro,” like he was surprised, then opened even wider, his stark shocked staring eyes. His glasses were blown away shattered and gone.

Blood was steadily rhythmically pumping from a small, neat hole in his forehead, blood filled in his eye sockets, and he changed from Jinrin to a monster I never knew.

I had no time to think what had just happened for at that moment a dark shadow filled the foxhole.

10

As I Looked up, a man, dressed in camouflage, holding a rifle, cautiously crept up and stood at the edge of the foxhole looking down at me. Beside him was a large dark dog silently staring at me, his lips pulled back showing gleaming teeth. He was deeply growling and obviously was well trained, he didn’t move a muscle, just stared at me like he would tear my face off if I tried to run. “KAISER, stay,” the man said softly. His voice sounded kind. It was between me and the other dog. I started to piss; I was so frightened by what was happening even though I didn’t want to. Pissing I do in private, but I was completely unhinged. We dogs piss to proudly mark our territory, to let other dogs know that we own this spot. But any dog that smell THIS piss would have one thought, this dog was scared witless, and so I was.

I growled ferociously, screaming really, baring my teeth, barking my most horrible bark.

“The only good Nip, so they say, is a dead one and this is a good Nip, got him between the eyes.” I just aimed between the glasses, that’s what gave him away, the moon’s reflection from the glasses. If the moon hadn’t broken out at that exact moment, I might be the dead one. Hey Mud Hole come here, take a gander, you want his gold teeth? A rich nip.”

The man started to laugh then stopped. He called to another man with a radio on his back, “hey Nez get over here. There is a little white dog in with the dead Jap.”

“I wouldn’t want to touch that little fellow!” chuckled Nez. “He looks meaner than snot. What the hell, there is another dog in there as well, he looks dead though. He is so muddy and wet I can’t tell what kind of dog he is.”

“Big son of a bitch though,” Chuck said, “I used to have a dog like that up in the high Sierras.”

“The Hell you say.” Mud Hole said. They talked and of course, I couldn’t understand a word they said. I thought, I have met the Hakujin, the white devils, I have met the enemy, and can now say they smelled, they stunk, they were loud, and surprisingly not threatening.

Just as I was thinking about how to make a leap out of that foxhole and escape, the big guy, Chuck, jumped down and threw his coat over me, it was dry and warm, and smelled like sweat and tobacco. I never saw Jinrin again and never heard Japanese, my home language, again.

We dogs in this world are doers and like to participate, we may not be able to speak the human language, but we have a vast language of our own that you humans can only guess at.

When all around us, we of the dog family can only guess at what it is that you humans are trying to say. Your human voice becomes to us dogs, a bird cry, a groan, a scream at which meaning we can only guess. My problem was additionally vexed since I only knew Japanese.

We war dogs come from centuries of canine battles the world over and we understand much, though we can’t talk like humans we can and do understand you. War is in the marrow of our bones.

We often understand your feelings before you do. We dogs know your signs and hand commands, shouts, whistles, and clicks. We watch your eyes for meaning.

There is that oddity where you humans laugh baring your teeth in a so- called friendly manner. I have seen good, even great dogs beat to death, while their owners laughed though that is rare. Laughing humans make me uneasy, especially when I don’t know the language. We see your gums, we watch, in our language to bare one’s teeth is to be angry.

Our hearing is very acute; you utter some words, and we are left to wonder what the meaning is. We war dogs are superbly trained we watch and listen for intruders, how to scent them even to see snipers up in trees. We can swim, parachute out of planes, crawl into caves, attack, alert our squad, guard prisoners, carry messages and, of course, hunt and locate the enemy, we can do much, not to mention that the lamest dog can outrun any human. We are low and fast.

The night Jinrin was killed, I could hear and smell the enemy in the Jungle way before Jinrin did. When I was unwrapped from the jacket and opened my eyes, we were in a plane, I had been in planes before, they are all noisy.

Mud Hole and Chuck, strapped into their seats were talking. Nez was left behind at the air strip. “Why do you suppose the Japs had so many dogs?” asked Mud Hole.

“Why you know the answer as well as I do Mud Hole, so their men can sleep, same as us,” and here he sat up straight, “they also can carry messages in the dark and kill japs when possible.”

The huge black dog, named Kaiser, slept with his heavy head on his massive front paws, one of which rested on a large bone.

The plane droned on into the murky night while Chuck and Mud Hole smoked cigars and talked. Chuck laughed and said “Hey, Mud Hole remember how Captain Carlson saw you drinking from that muddy stagnant ditch back there in New Guinea, which was how you got your name don’t you know?” Mud Hole just laughed and held up a bracelet made from Jinrin’s teeth. “My name I don’t mind it because I am behind it, it’s the nips that I kill that counts,” he said in a sing-song voice laughing.

I didn’t hear the rest of the story besides, as I said, I can only understand Japanese anyway. As they mumbled and guffawed, I drifted off once again into a deep and scary sleep.

“Someone will remember us.”

I say, “Even in another time.”

Watch for Part 2 in June, 2022!